|

High Priority Corridor 3 Statutory DescriptionEast-West Transamerica Corridor commencing on the Atlantic Coast in the Hampton Roads area going westward across Virginia to the vicinity of Lynchburg, Virginia, continuing west to serve Roanoke and then to a West Virginia corridor centered around Beckley to Welch as part of the Coalfields Expressway described in section 1069(v), then to Williamson sharing a common corridor with the I-73/74 Corridor (referred to in item 12 of the table contained in subsection (f)), then to a Kentucky Corridor centered on the cities of Pikeville, Jenkins, Hazard, London, Somerset; then generally following the Louie B. Nunn Parkway corridor [I-66] from Somerset to Columbia, to I-65; then to Bowling Green, Hopkinsville, Benton, and Paducah, into Illinois, and into Missouri and exiting western Missouri and moving westward across southern Kansas. I-66 Trans America Corridor HistoryThe I-66 East-West Trans America Corridor 3 was first authorized by Congress in 1995, and still exist in federal law, however the last I-66 environmental study was cancelled by the FHWA in Illinois and Missouri in 2015, cancelling any future planning of an I-66 western extension. The original concept proposed in the 1980's envisioned building a transcontinental interstate route the generally followed the famous US 60 "Route 66" from Missouri to California. The first proposal started from the existing I-66 in Virginia, through West Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, Kansas, New Mexico, Arizona and California. This original proposal was never enacted formally by Congress and overall, interest in this concept never developed in the Western states due to the extremely high cost of the routing the highway through very isolated land, even the Death Valley National Monument, which was quickly opposed by the Interior Department. I-66 designation along US 460 in Virginia was logical and since it required decommisioning the existing I-66 route number in northern Virginia. The Virginia Department of Transportation never seriously pursued the I-66 Trans America concept, instead it proceeded to simply four-laned the majority of US 460 with some freeway bypass sections and building the US 460 freeway to Blacksburg from I-81. Kentucky led the planning of I-66 to use two existing parkways in the southern part of the state, then generally follow US 119 along a new terrain route to the planned I-73/I-74/US 52 King Coal Highway in West Virginia. The plan required that I-66 least terminate at I-73/I-74 since Interstates must terminate with another Interstate by law. The Cancellation of Future I-66 in Kentucky and IllinoisWest Virginia put the I-73/I-74 upgrade of US 52 on indefinite hold because of no guaranteed fund, low traffic projections and low economic benefit. KYTC had no justification to fund I-66 for the next 30 years as I-73/I-74 was put off indefinitely. In addition, the environmental impact versus economic or traffic benefits for a new terrain I-66 from Somerset Kentucky to West Virginia made the its need questionable by the early 2000's. Planning for the I-66 concept was ended in Kentucky in 2005 and in Illinois and Missouri in 2015. Cancellation of the project was based on lack of funding and environmental opposition from the National Park Service because of unnecessary routing through several national forests and the Appalachian Mountains in Kentucky and West Virginia. Plans for I-66 began to be withdrawn by the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet in 2005 with the realization that funding was impossible even over the long term with higher priority Interstate projects for I-69 and the Ohio River Bridges for I-65, I-265, and I-75. The end of the I-66 project came finally when the FHWA, the Illinois DOT, and Missouri DOT agreed to cancel the Corridor 66 Environmental Impact Study in 2015. .jpg)

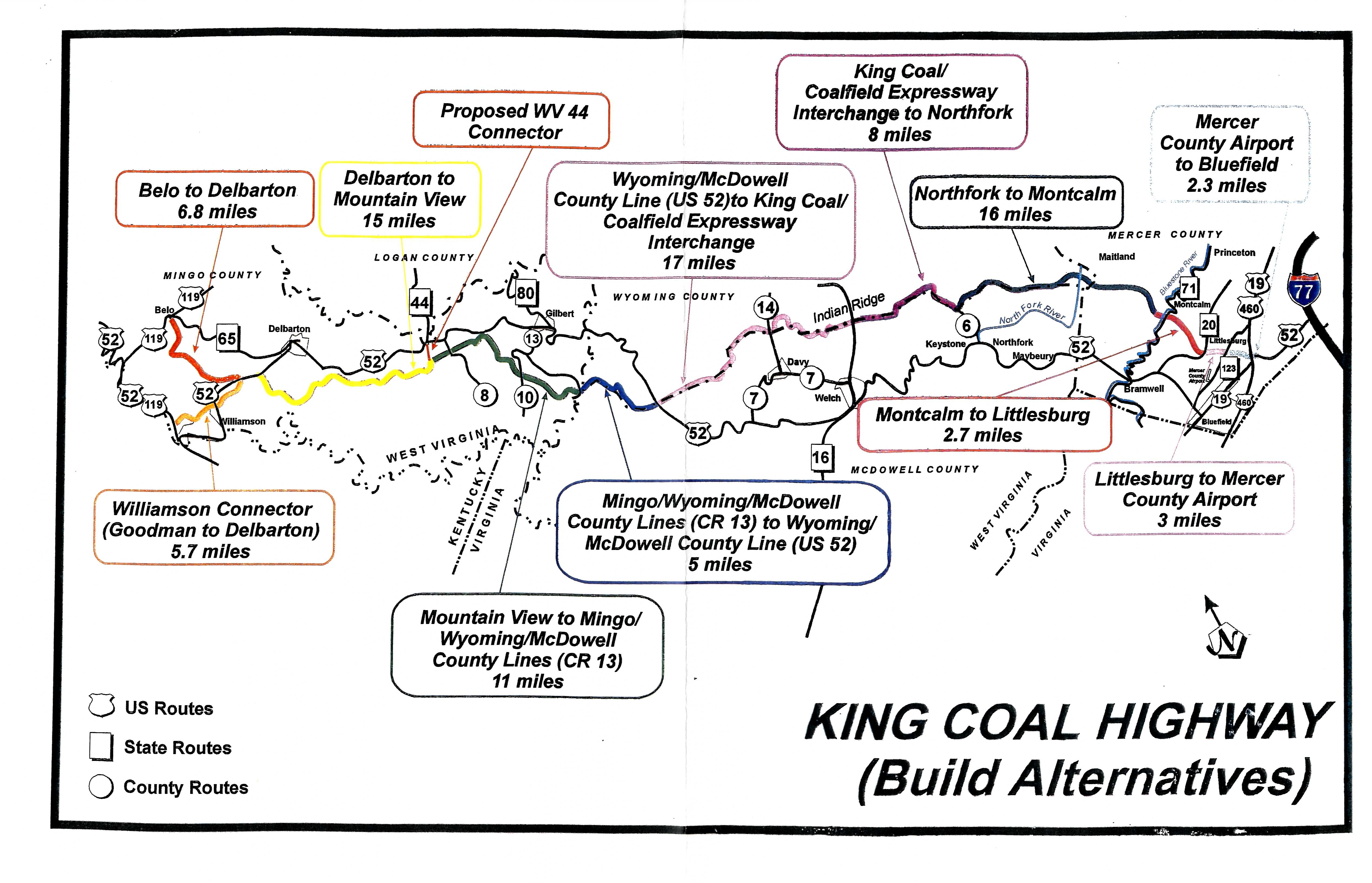

US 52 King Coal HighwayThe King Coal Highway Authority was established by the West Virginia Legislature in March of 1999 to promote and advance the construction of a four-lane divided highway that will become the new routing for US 52 through McDowell, Mercer, Mingo, Wyoming and Wayne counties replacing the existing US Route 52. The Authority coordinates with counties, municipalities, state and federal agencies, public nonprofit corporations, private corporations, associations, partnerships and individuals for the purpose of planning, assisting and establishing recreational, tourism, industrial, economic and community development of the King Coal Highway for the benefit of West Virginians.

The West Virginia Division of Highways (WVDOH) plans to build the highway from a point near Williamson – at the intersection of WV 65 and US 119 – to Interstate 77 at its US 52 interchange in the Bluefield area (see map). After evaluating six alternative routes for the highway and considering public comments from a May 1998 public information workshop, WVDOH selected a Preferred Alternative. By the year 2020, engineers estimate the new highway would cut travel time on the existing US 52 to almost in half. The Preferred Alternative plan also includes a 4-lane connector, nearly five miles long, to improve access into Williamson. The connector would also provide access to the Mingo County Airport. The Preferred Alternative was chosen on the basis of its ability to meet the needs of the project while minimizing impact on the natural, physical and social environments. This selected route avoids the greatest number of archaeological resources and has the least impact on businesses and residences. This Preferred Alternative, however, remains "preliminary" until the completion of the entire public involvement process. The King Coal Highway will be a four-lane divided highway with partially controlled access between Williamson and Bluefield. It ultimately will cover approximately 90 miles of mountainous southern West Virginia, opening it up to faster, safer transportation. The route was designated as a High Priority Corridor in the National Highway System in the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 and included in the Interstate system as Future Interstate 73 and Interstate 74 Corridor. Michigan and Ohio widthdrew their support for I-73 and I-74. North Carolina completed sections of both I-73 and I-74. South Carolina is planning to complete part of I-73 from I-95 to Myrtle Beach. Virginia withdrew plans to build I-73 from Roanoke to the North Carolina border. West Virginia ended not only its plans to ever build I-73 or I-74 but plans no further construction of the U.S. 52 King Coal Highway after completing small sections in ths state.

US 52 TOLSIA HighwayThe TOLSIA Highway was the portion of U.S. 52 in southern West Virginia between Kenova in Wayne County and Williamson in Mingo County. The acronym is taken from the "Tug-Ohio-Levisa-Sandy Improvement Association", a group of local business people and community leaders who successfully lobbied in the 1950s and 1960s to have a new roadway constructed along the Big Sandy River. After the new road was built, the U.S. 52 designation which previously had applied to the road connecting Huntington and Crum was moved to the new road. The old road was renumbered as U.S. 152. State and federal officials pressed ahead with plans for upgrading it from a two-lane roadway to a four-lane divided highway. The new, upgraded road will be built in three sections, the first from Kenova to Fort Gay, the second from Fort Gay to Crum, and the third from Crum to Kermit. Construction on the upgrade, estimated to cost more than $800 million, began in 1996 and was expected to take a decade or longer to complete.

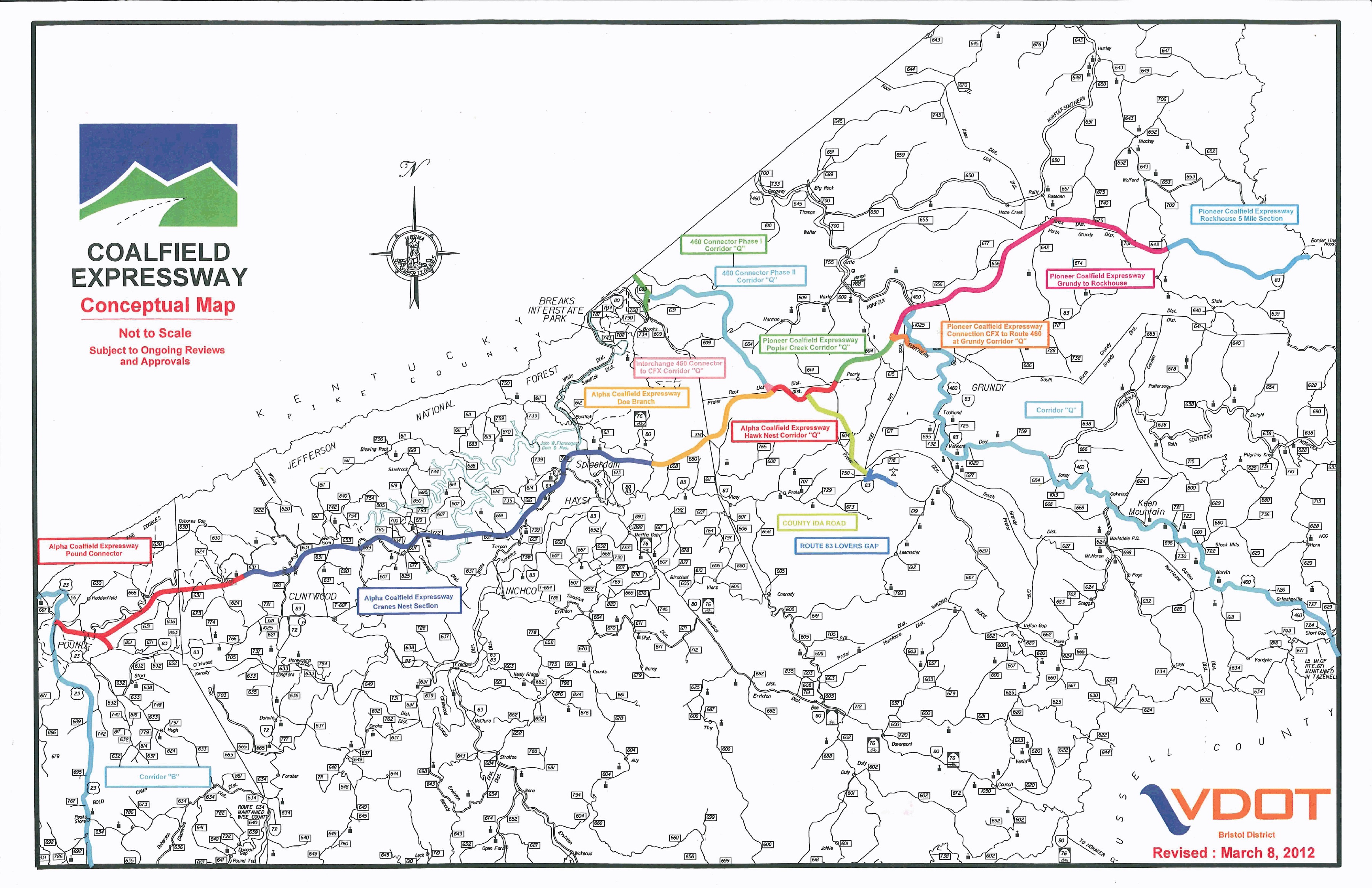

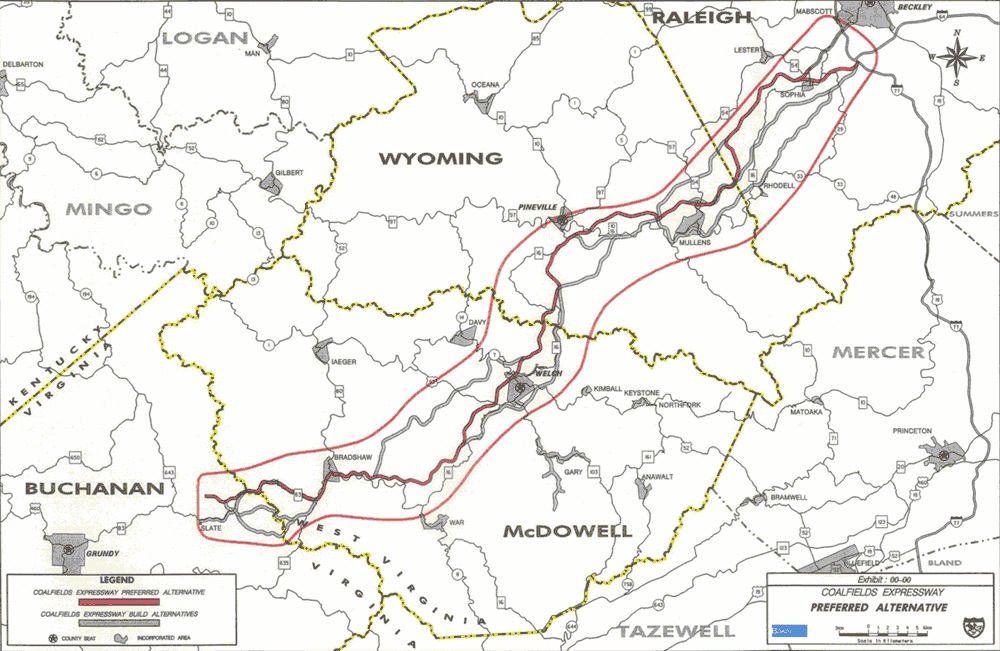

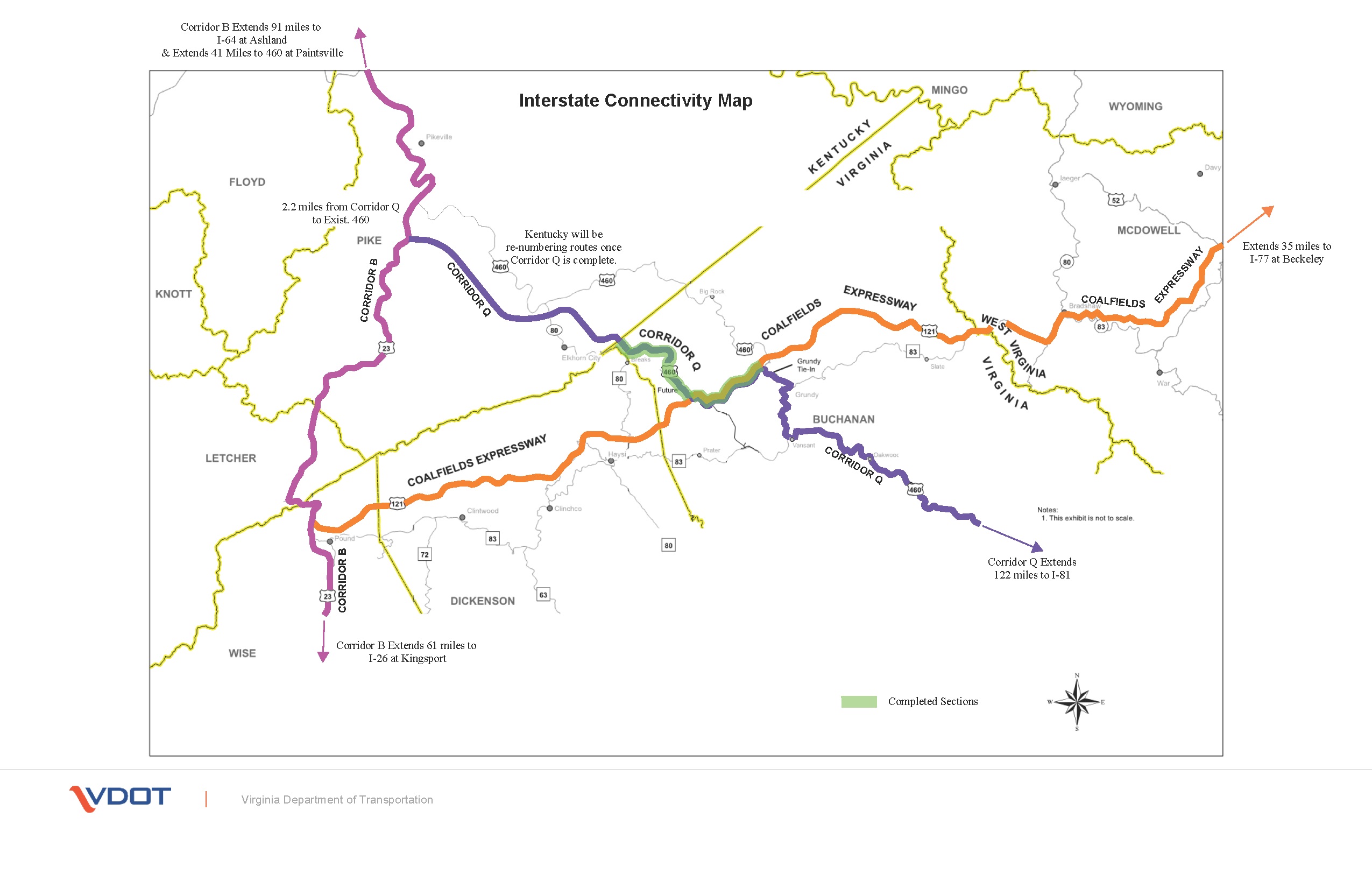

US 121 Coalfields ExpresswayThe Coalfields Expressway project was initiated September 2002. The goal is to provide a multi-lane expressway, with partial control of access, connecting I-64/I-77 West Virginia Turnpike at Beckley, West Virginia (WV) to US 23 ADHS Corridor B at Slate, Virginia (VA). This corridor through the Appalachian Mountains of southern WV and western VA is expected to promote economic development opportunities for this region. In West Virginia, the Coalfields Expressway will be about 65 miles long and in VA, the length of the corridor will be about 50 miles. The steep terrain and rugged topography prominent in this region result in high construction costs for site development for businesses and residences, for utility installation, and for transportation facilities. The existing two-lane roadways have many deficiencies for today's transportation needs, including a high percentage of "No Passing" zones, many steep grades and areas of reduced speeds through many communities and school zones, all of which affects travel time and cost of transport of commodities to and from the region. Most of this area developed as a result of the coal industry, the influence of which has been so strong that it has affected land use, population characteristics, community services, housing development, the economy, and transportation opportunities. Over the last few decades, however, portions of this region have experienced a decline in population, employment, and economic opportunities due to changes in the coal industry. The need for the construction of the Coalfields Expressway may be attributed to identified deficiencies regarding three basic transportation issues: 1) existing roadway conditions; 2) safety; and 3) economic opportunities. The highway corridor is characterized by steep grades, sharp horizontal curves, constant changes in driving conditions, and the presence of communities, schools, and “No Passing” zones. In addition, poor sight distance, numerous access points from secondary roads, and both residential and commercial driveways combine to create safety deficiencies and impede travel and efficiency. Warning signs and speed limit reductions are used as a means to alert drivers of potentially dangerous conditions. Along the Coalfields Expressway corridor, the existing traveled way of the WV portion is about 92 miles, most of which is two lanes. After construction is complete, however, the corridor length will be reduced to about 65 miles of four-lane highway. The corridor traverses mountainous areas characterized by steep, narrow, winding stream valleys. In many areas, the roads were constructed parallel to streams to avoid substantial excavations. This type of construction resulted in sharp horizontal curves that do not satisfy the 50-mph design speed criteria identified by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). Winding routes and steep grades impede truck flow and automobiles traveling behind these trucks. Steep grades also create sight distance problems for approaching vehicles that cannot see the slow-moving or stopped line of vehicles. The coal industry is the largest component of the local economy and is anticipated to remain so in the future, it is important to provide efficient coal truck passage within and through this region. In addition to enhancing coal operations, the improvement of Coalfields Expressway will facilitate the achievement of other long-term economic development goals of community leaders in this area, which include attracting other suitable industries, improving the infrastructure, and providing better jobs. The Coalfields Expressway Authority published in December 2006 an Economic Impact Study concerning the Expressway. The conclusions of that study indicate that the Coalfields Expressway is expected to allow for its counties to generate increased economic growth and to be connected to one of the fastest growing areas in the region (Raleigh County), and the data confirm that the presence of the Coalfields Expressway would make a significant improvement in the region's economic conditions. The preferred alternative alignment of the Expressway traverses land with existing coal mining. The state highway departments and the Coalfields Expressway Authority are forming partnerships to facilitate the construction to rough grade alignment of the Expressway as part of a Post-Mining Land Use or other coal mining project. These partnerships will significantly reduce the cost of the Expressway, while expediting the completion of sections of the Expressway. Congress authorized the construction of the Appalachian Development Highway System (ADHS) in 1965. The system was designed to generate economic development in previously isolated areas, supplement the interstate system, connect Appalachia to the interstate system, and provide access to areas within the region as well as to markets in the rest of the nation. The Coalfields Expressway not only intersects the ADHS, part of its path actually overlays a portion of ADHS Corridor Q near the Buchanan County town of Grundy. Coalfields Expressway and Corridor Q are separate but related transportation initiatives. The estimated const are $5.1 billion using traditional construction methods and $2.8 billion using coal synergy. While there has been widespread and long-standing support for improving highways in the Appalachian region, the cost of building roads has been a major stumbling block, especially as governments struggled with budget constraints. Virginia lawmakers approved legislation in the mid-1990s to allow the Commonwealth to consider creative funding and construction solutions with the private sector. About a decade later, the emergence of “coal synergy” would finally set the stage to make it feasible to build the Coalfields Expressway and accelerate completion of Corridor Q. The process of coal synergy reduces road building costs substantially by using larger-scale earth moving equipment from coal companies to prepare the road bed to rough grade, and allowing the companies to recover marketable coal reserves during the road bed preparation. It is projected that coal synergy would reduce the cost of building CFX by approximately 45% compared to traditional highway construction methods. Status in Virginia: January 16, 2013 - VDOT presented Location Public Hearing information for the Coalfields Expressway Environmental Sections I and II to the Commonwealth Transportation Board. February 20, 2013 - Virginia's Commonwealth Transportation Board voted to approve the new location of the Coalfields Expressway Environmental Sections I and II. May 22, 2014 - FHWA requested a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement for the Coalfields Expressway Section II. VDOT revised the environmental assessment accordingly and send it to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) for a final decision. February 2015 - Virginia's Commonwealth Transportation Board passed a resolution to approve an alignment change for 4.1 miles of the Route 121 (Coalfields Expressway) that overlaps with a section of US Route 460/Corridor Q.

US 460 Corridor Q Expressway in Virginia |

|---|---|

|

.jpg)

I-50/I-60/I-70 Transcontinental Pioneer Historical CorridorThe new Trans America Corridor runs from Norfolk Virginia to San Francisco California. The description of the corridor generally follows the following existing highway routes:

|

Virginia

|

I-50, U.S. 460 Corridor Q, U.S. 121 Coalfields ExpresswaysThe old I-66 concept was not feasible since it required an new terrain route to US 52 King Coal Highway which had to be converted also to I-73/I-74, which has likewise been on indefinite hold in West Virginia. The new US 460 Corridor Q Expressway and US 121 Coalfields Expressway under construction in Virginia and Kentucky will cross the Appalachians as part of the Appalachian Highway Development System. US 460 Corridor Q Expressway will be a new modern four-lane divided highway that can upgraded to Interstate Highway standards to accomodate I-50. Begining in Virginia Beach Virginia, I-50 would follow I-264 to Norfolk. I-50 continues west along US 460 to Suffolk, Petersburg, Lychburg, and I-540/I-81 in Roanoke. I-50 branches from I-81 along the US 460 freeway to Blackburg (built to accomodate the Trans America Highway) and finally into West Virginia. An alternative route is the keep following US 460 to Kentucky. After briefly passing through West Viginia, I-50 follows the planned US 121 Coalfields Expressway to Grundy, then the new US 460 Corridor Q Expressway into Kentucky |

West Viginia

|

I-50 follows U.S. 52 King Coal Highway and U.S. 460In West Viginia, I-50 connects to the planned US 52 King Coal Highway then U.S. 460 into Virginia. I-66 follows U.S. 48 Corridor H, U.S. 33, then U.S. 35. I-68 extends west to WV 2 along the Ohio River to U.S. 50 around Parkersburg. |

Kentucky

|

I-50 follows Louis Nunn Parkway, Hal Rogers Parkway, King Coal HighwayI-50 follows the original "I-66 Southern Kentucky Corridor" route, U.S. 68 to Hopkinsville and I-24 to Paducah then a new terrain route and bridge across the Mississippi River into Missouri.

I-50 follows Louis Nunn Parkway, Hal Rogers Parkway, Corridor QI-50 follows U.S. 121 and U.S. 460 Corridor Q in Virginia to the part of original "I-66 Southern Kentucky Corridor" route west of U.S. 23, then U.S. 68 to Hopkinsville and I-24 to Paducah along a new terrain route and bridge across the Mississippi River into Missouri. |

Missouri

|

I-50The I-50 Trans America Highway intersects I-57 in Missouri and run concurrent with US 60 which will be converted to the Future I-57 freeway. I-50 and I-57 seperate at Poplar Bluff, then along the US 60 four-lane that will be converted to the I-50 freeway to I-44 in Springfield. West of Springfield, the Trans America Highway is designated as I-60 following a new terrain route far north of Joplin to connect to US 400 into Kansas. |

Kansas

|

I-50, I-60In Kansas, I-50 follows U.S. 400 through Kansas to Wichita Kansas, then U.S. 54 to the Oklahoma border. I-60 follows U.S. 50 corridor from I-50 to the Colorado border. |

Colorado

|

.jpg)

I-60, I-70I-60 generally follows US 50 to Pueblo Colorado. I-60 continues along US 50 to terminate in Grand Junction. From Grand Junction, the Trans America Corridor includes the existing I-70 into Utah. |

Utah

|

I-70 West ExtensionThe I-70 Trans America Corridor continues to Salina Utah. From Salina a new terrain I-70 extension could follow US 50 or could continue to the existing I-70/I-15 interchange. The now I-70 Trans America Corridor would need a new terrain route to US 50 before continuing generally following the US 50 corridor through Utah into Nevada. |

Nevada, California

|

I-70 West Extension, I-170The I-70 Trans America Corridor follows US 50 through Carson City Nevada. I-70 bypasses south of Lake Tahoe following US 395 (Future I-11) and NV 308 to enter California along CA 88. The I-70 Trans America Corridor enters California south of Lake Tahoe along US 50 through the Sierra Nevada mountain's. The new I-70 should include new tunnels and viaducts to make sections of the route virtually snow-free, safe from mudslides, rockslides, d the flooding of the American River canyon that US 50 runs through. I-70 would connect to the the existing US 50 freeway in Sacramento, and would form a continuous transcontinental route with I-80 from the Pacific ports in San Francisco Bay to the Atlantic port in Norfolk/Chesapeake Virginia. This provides drivers with a potentially snow-free alternate to the dangerous snow covered Donner Pass along I-80 in the winter. |

Future I-50/I-60/I-70 Transcontinental Pioneer Corridor

|

Future I-18 Acadian-Creole-Spanish Trail Historical Corridor, Future I-53/I-57 Mississippi River Mound Builders Corridor

|

|---|---|

Future I-66/I-68 Ohio River Mound Builders Historical Corridor

|

Future I-63 Emancipation Underground Railroad Historical Corridor

|

Future I-14 Gulf Coast Strategic Highway Corridor

|

Future I-76 Lincoln Highway Historical Corridor

|

Future I-49 Corridor

|

Future I-31 Great Plains Corridor, Future I-27 Ports-to-Plains Corridor

|

Future I-42 Conversion of U.S. 412 and U.S. 70

|

Future I-69

|